Rehabbing Sammy Davis, Jr. in PBS' I've Gotta Be Me

02/19/19 13:47

By ED BARK

@unclebarkycom on Twitter

The complexities of Sammy Davis, Jr. run far deeper than that hug of Richard Nixon or those deferential, knee-slapping, “with your kind permission” appearances on a variety of talk shows.

PBS’ venerable American Masters series gets at some of them in Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me (Tuesday, Feb. 19th from 8 to 10 p.m. central). It’s a workmanlike and long overdue look at a misunderstood mega-talent who’s been dead for nearly 30 years and still is yet to get a scripted feature film bio.

“In the end he was deeply hurt that he was seen as an Uncle Tom,” says African-American essayist Gerald Early.

Directed by Sam Pollard, Gotta Be Me is rich in archival clips of performances and Davis’ lesser seen introspective interviews with the likes of David Frost and Arsenio Hall. But it’s somewhat impoverished in terms of what drove Davis to the heights and depths of his fame.

Unfortunately, the nearly two-hour film (including bonus performance footage at the end) comes and goes without any input from African-American author Wil Haygood. His 2003 book, In Black and White: The Life of Sammy Davis, Jr., is the definitive biography of its subject. Haygood in part strove to correct what he believed to be the copious fiction presented in 1965’s Yes I Can, a bestseller in which Davis collaborated with journalist/publicist Burt Boyar and his wife, Jane Boyar.

Burt Boyar, who died in 2018, lived long enough to be interviewed for Gotta Be Me. And his comments are spread throughout the film. But Haygood, or any mention of his book, are entirely left out. I’ve read it. It’s monumental.

On the flip side, filmmaker Pollard deserves credit for finding and including actress Paula Wayne, likewise recently deceased. Wayne, who still very much speaks her mind in Gotta Be Me, co-starred with Davis in his hit 1964 show Golden Boy. Their full on the lips interracial kiss was a first -- for Broadway, TV or the big screen.

“I said, ‘Yeah, so? Let’s do it,” Wayne recalls before Davis asked her if she was prepared for the “aftermath.”

“What aftermath?!” Wayne remember saying incredulously.

The aftermath included picketing of subsequent performances. And Wayne recalls hearing of herself: “She’s the one that kissed the nigger . . . How’s that grab ya? It was awful.”

Earlier in his career, Davis was kissed off by newly elected President John F. Kennedy, who disinvited him at the last minute from performing at his 1961 inaugural gala along with fellow Rat Packer Frank Sinatra. Davis was newly married to Swedish actress May Britt, and JFK reportedly didn’t want to offend Southern Democrats.

“I’m confused as (to) why Frank Sinatra didn’t stand up for him,” Wayne says. ”Wrong on so many levels. And he was desperately hurt.”

The embrace of Nixon, who had gone out of his way to befriend Davis, is better understood in this context. As documented in Haygood’s aforementioned book (but not in Gotta Be Me), Nixon had been an early adapter who as a U.S. Senator had gone out of his way to see Davis’ show at the Copa club and later meet him backstage. As President, Nixon also invited Davis and his third wife, Altovise (who’s never mentioned at all in the film), to be the first African-Americans to sleep in the storied Lincoln bedroom. They accepted.

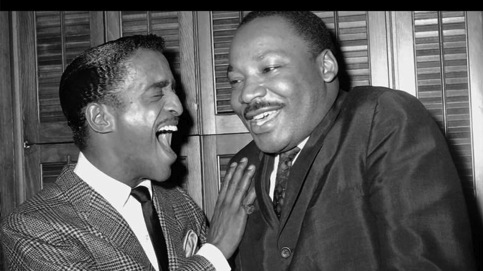

Nixon gave Davis “high regard as a person,” Early says. And the eager-to-please entertainer lapped it up, later to his regret. “The Hug,” during an event at the 1972 Republican National Convention in Miami, made Davis a pariah among many in the black community. All but forgotten was his earlier embrace of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., on whose behalf he raised money and attended civil rights rallies.

“His commitment was never fully recognized historically,” says Harry Belafonte, who on the other hand is critical of the racial humor aimed at Davis during Rat Pack appearances with Sinatra, Dean Martin and Joey Bishop.

Billy Crystal dismisses this as “different times . . . That was part of their thing. He was a good sport about it.” (No mention is made of Crystal wearing blackface to do his recurrent Sammy Davis impressions, most recently during the opening to the 2012 Oscars.)

Gotta Be Me also addresses the brutal racism Davis encountered while in the military, his lack of any formal education during a show biz career that began at age three and his formative years with The Will Mastin Trio, which also included his father and uncle. But unlike Haygood’s book, nothing is said of Davis’ increasingly desperate attempts to break away from his father’s control.

Director Pollard has divided his film into segments ranging from “Patriot” to “Activist” to “Leading Man.” But there’s also ample room for showcasing the subject’s prodigious skills as a dancer, singer and the first black artist to do impressions of white performers such as Humphrey Bogart and James Stewart.

In February of 1990, shortly before his death, Davis’ 60 years in show business were commemorated in a three-hour ABC special that attracted the biggest gathering of show business legends before or since. Gotta Be Me thankfully includes Michael Jackson’s song in his honor (“You were there before we came. You took the hurt, you took the shame”) and Davis’ show-stopping tap dance square-off with the late Gregory Hines.

Sammy Davis Jr. died on May 16, 1990 at the age of 64. In this view, his enormous talent and under-appreciated trailblazing far overshadow his missteps in pursuit of fame, fortune and above all, acceptance.

“I have no desire to be the boy next door,” he once said of his extravagant spending and audacious wardrobe. The man who shocked Archie Bunker with a smooch on the cheek during the most famous episode of All In the Family deserves to be remembered in full for enduring, surviving and in many ways, conquering. Gotta Be Me re-sets his table. It’s about time, but certainly not nearly enough.

GRADE: B+

Email comments or questions to: unclebarky@verizon.net