Finfrock stepping down as NBC5's chief meteorologist, but will still have his foot in

01/31/18 08:26 AM

By ED BARK

@unclebarkycom on Twitter

He succeeded a legend and then became one himself.

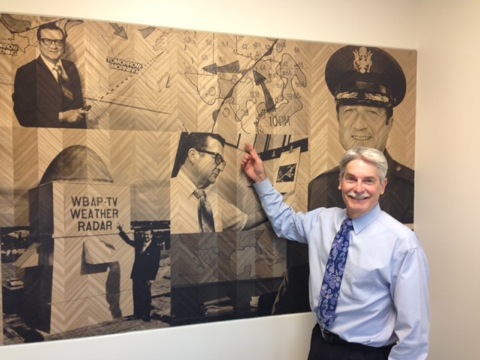

From Harold Taft to David Finfrock -- and the list doesn’t go on and on. They have been the only two chief meteorologists in the 70-year history of KXAS-TV (which began as WBAP-TV and now is promoted as NBC5).

As of Thursday, Feb. 1st, that will change. Finfrock isn’t leaving, but he’s cutting back to a part-time forecaster who will work roughly 100 days a year on a pay-per-day basis. The new chief is Rick Mitchell, who joined NBC5 in August 2012 and has been the weekday 10 p.m. meteorologist ever since.

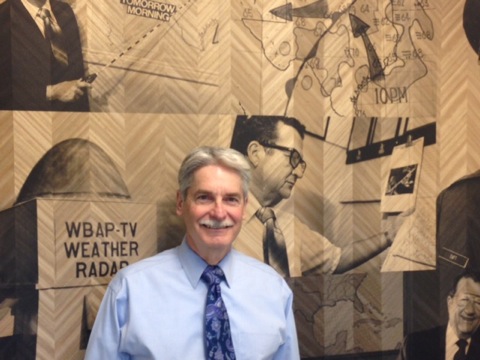

Finfrock, who turns 65 in May, says “it’s the best of both worlds for me” and a voluntary move that meets his goals of having more time off while also staying in the game.

“That’s one thing I was looking forward to -- the flexibility and scheduling,” he says during an interview at NBC5’s Fort Worth studios. “I enjoy the work. Most of my friends are here at the TV station. And I would hate to just walk out the door and not come back.”

He signed his last long-term deal in 2012 and it was set to expire on June 1st of this year. But Finfrock says he opted for a Dec. 31 “retirement” due to imminent changes in the station’s health insurance provisions that would have affected his wife of 40 years, Shari Finfrock. In what so far is “kind of a handshake deal,” Finfrock is “more likely to be in” on Wednesdays through Fridays. But if bad weather hits, he’ll pitch in on other days. Because of a long-planned vacation trip, he’ll also miss most of the month of November.

“If everything goes well, it’ll probably be the same situation next year,” he says.

Station management asked him about titles and suggested he could be NBC5’s “senior chief meteorologist,” Finfrock says. “But you can’t have two chiefs,” he added, so they settled on the title of “senior meteorologist.”

“It may sound like a cliche, but I’m truly honored to be taking over for David,” Mitchell says. “To be only the third chief meteorologist in the history of KXAS is humbling. Both Harold Taft and David have set the bar high, so I have my work cut out for me. I’m confident that my 30 years of experience will serve me well.”

Finfrock pinpoints his “first day in the building” as Dec. 22, 1975, but isn’t entirely certain about the exact date of his inaugural on-air appearance. On one of the “first few days of January” 1976, though, Taft walked up to him during a commercial break for the noon newscast and said, “Why don’t you do it today.”

“I had two minutes warning for my television debut,” he recalls. “I was nervous. It took me about six months, really, to get comfortable in front of the camera.”

Taft did him a favor, though, with his spur-of-the-moment directive, Finfrock says. “I didn’t have to think about it overnight.”

Until the early 1980s, Taft and Finfrock stuck to what now seems like a stone age approach. They hand-drew their maps for each newscast. There was one for Texas, another for the U.S. and a third “forecast map.” Temperatures were posted with a Marks-A-Lot pen just before the weather segment began, with Finfrock hurrying to a teletype machine to get the latest highs and lows.

Taft, who was an Army officer during World War II, often acted as though he was still in uniform. Yes was “Affirmative,” No was “Negative,” and he went “on leave,” not vacation.

“I never had any problems with Harold,” Finfrock says. “He was a stickler for doing things by the book. He had that military bearing, which I definitely do not.”

So how did Finfrock, “extraordinarily shy” as a young man, and the stern, imposing Taft hook up in the first place? It’s still quite a story.

Finfrock, who grew up in Houston, graduated from Texas A&M in May 1975 with a bachelor of science degree in meteorology. He then spent the summer in Juneau, Alaska, doing field research in geology, geophysics and meteorology.

A full fellowship for graduate studies awaited him at Texas A&M, where he resumed studies that fall. Then came a phone call from someone “I never heard of.” It was Taft. He’d been looking at various job applications on public file at the National Weather Service’s southern regional office in Fort Worth. Finfrock caught his eye -- along with a number of other applicants. Would he like to audition at KXAS?

“I almost didn’t come,” Finfrock says. He had put off taking a mandatory public speaking class until his senior year as an undergrad at A&M. Couldn’t he just take a second semester of Russian instead? Told no, he girded himself and to his amazement, got a grade of A. During the course of the course, he learned “if you know your topic ahead of time, your fear tends to go away.”

So the idea of being on television wasn’t as daunting when Taft called. And after an intoxicating summer in Alaska, “sitting in a classroom again was kind of stultifying,” Finfrock says. “I was ready to get on with my life.”

The KXAS audition didn’t go well -- or so Finfrock thought. Initially seated at an anchor desk on a raised platform about six inches high, he was required to stand up and walk a short distance to the “weather wall.” When Finfrock arose and pushed the chair back, it toppled off the platform, making a “tremendous crashing sound.” Finfrock stayed on his feet and did the segment. But at that instant, he figured he’d blown it.

Taft chose him anyway, and a couple of years later, Finfrock asked him why.

Taft told him he was impressed with how the kid reacted calmly to a little duress and “if you can smoothly handle that, you should be able to handle just about anything on the air.” Otherwise the applicants were pretty much even in their qualifications, Taft said.

“So if my chair hadn’t toppled over, I might not have gotten the job,” Finfrock says. “I might be studying climate science on a glacier somewhere right now.” (A bit later, Finfrock accidentally knocks over his interviewer’s coffee cup. Just saying.)

Finfrock initially was paid monthly with a check from Harold E. Taft & Associates. He worked Mondays through Fridays plus Saturdays and had no holidays, vacation time or health benefits. Taft received “a monthly sum (from KXAS) to provide all the weather services for the station,” Finfrock remembers. “So it behooved him to hire someone who didn’t get a big paycheck. But it got my foot in the door.”

Taft died on Sept. 27, 1991 of cancer, continuing to work up until six weeks before he passed. Toward the end, “he would lie down on the floor for an hour to regain his strength,” Finfrock says. “There was no quit in him.”

Finfrock then became chief meteorologist. By that time, hand-drawn weather maps were very much a blast from the past while new tools continued to make short-term forecasting more accurate than ever.

For accuracy’s sake, Taft resisted doing more than a two-day forecast while rival stations were doing five-day predictions. A couple of years after his death, Finfrock joined in the five-day outlooks, which now have expanded to 10 days. The latter two or three days are “more guidance than anything else,” he concedes. But “we do a whole lot better than we did before” with 48-hour forecasts, which seldom miss anymore.

Finfrock says that climate change basically is an undeniable reality, with the last three years getting progressively warmer.

“The trend line is just going up,” he says. “Perhaps there is some natural fluctuation going on. I wouldn’t totally discount that.”

But with carbon dioxide levels steadily on the rise, “if there is any natural warming, we are adding to it by human causes. It would just make common sense to not make it any worse.”

What seems to be an increasing frequency of heavier storms is also “something we ought to get our hands on,” he says.

Finfrock continues to relish the great outdoors, finding it boring to exercise on a treadmill. He’d much rather cut brush and split firewood on the Finfrocks’ 100-acre ranch, which they own in addition to their main home. “That’s how I stay in shape, not only physically but mentally,” he says.

David and Shari have two children, Jennifer, 44, and Ryan, 39. He met his wife in Fort Worth, which never would have happened had Taft not called him and changed his career path in ways that Finfrock never imagined.

They remain interlocked, disparate in personalities but dedicated to the cause of presenting the weather without any artificial breeziness. Taft’s tutelage is ingrained, and it’s still evident that Finfrock would never want to disappoint him.

“I came of age watching Harold here,” he says. “He was my mentor.”

Email comments or questions to: unclebarky@verizon.net