HBO's Living in the Material World portrays George Harrison as much more than the "other Beatle"

10/05/11 12:53 PM

By ED BARK

Being the Third Wheel can get old in time, even when you're part of an all-powerful locomotive.

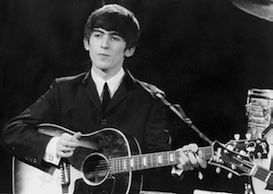

George Harrison, the mystical, "misunderstood," oft-stoic Beatle, wrote enough good songs to fully stock an upstanding greatest hits album. John Lennon and Paul McCartney were always the band's dynamic duo, though, with George on the inside looking in.

The two-part HBO documentary, George Harrison: Living in the Material World, at last gives him full-fledged star treatment -- and at the hands of Marvin Scorsese no less. The first 95 minutes are on Wednesday, Oct 5th (8 to to 9:35 p.m. central), with the concluding two hours on Thursday, Oct. 6th (8 to 10 p.m.). There will be repeats throughout the month, as well as availability on HBO's various On Demand outlets.

Much of the material "has never been seen or heard before," HBO says in publicity materials. That's the usual hook, with Scorsese and co-producer Olivia Harrison (his second wife) sifting through troves of stills, home movies and rare performance videos. Living in the Material World, which is an appreciably better film on Night 2, also includes fresh interviews with McCartney, Ringo Starr, Yoko Ono, George Martin, Eric Clapton and most surprisingly, legendary record producer/convicted murderer Phil Spector, who turns out to be a surprisingly interesting contributor.

Spector helped to produce Harrison's first post-Beatles album, 1970's "All Thing Must Pass." Harrison doesn't say this in the HBO film, but he's been quoted as stating, "I didn't have many tunes on Beatles records, so doing an album like All Things Must Pass was like going to the bathroom and letting it out."

Looking garish as usual -- but in reddish blonde bangs instead of the giant-sized Afro he sported in the courtroom -- Spector says that Harrison kept procrastinating on the album because he was unsure about ever releasing it. "Perfectionist is not the word," Spector says in a raspy voice. "Anyone can be a perfectionist. He was beyond that."

The triple album's best-known tune, "My Sweet Lord," became a No. 1 hit after Spector says he insisted that it be the first single over objections from just about everyone, including Harrison.

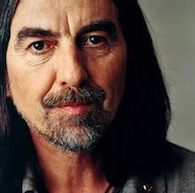

Scorsese often chooses to cut abruptly from one segment to another in a film that touches lightly on many pivotal events in The Beatles' incredible run. Much of this already has been detailed in numerous books and films, and this is after all a film about the oft-overlooked George, who died of cancer in 2001 at the age of 58. An older Harrison regularly speaks for himself in several talk-to-the-camera interviews, all of them in sharp color but unlabeled as to when they occurred.

The Beatle that most people never really knew likewise was trying to find himself. Meditation and Eastern music became his portals. The other Beatles gave both a bit of a fling, but Harrison became a true believer. In Thursday's Part 2, his close friendship with Ravi Shankar is brought vividly front and center. The famed sitar player became the impetus for 1971's All-Star Concert for Bangladesh after he told Harrison of the horrible conditions in the South Asian country.

Clapton, another close friend, also happened to be the bloke who started secretly seeing Harrison's first wife, Patti Boyd, while she and George were still married. He's candid about becoming "more and more obsessed" with Patti, and finally feeling the need to tell George about it.

"And he was kind of cavalier," Clapton recalls. "He said, 'Well, take her, she's yours.' "

Patti remembers it all quite differently, saying that Harrison became "furious" when he discovered the two of them at a party. She eventually married Clapton, but they too divorced. The film includes a brief excerpt from a press conference in which Harrison is asked about the triangle.

Clapton is still a friend and all-around great guy, Harrison says. "I'd rather she was with him than some dope."

George's music, both with and without The Beatles, is the film's real reason for being. And although Lennon and McCartney wrote the great majority of the material, Harrison certainly got his licks in with the likes of "If I Needed Someone" (from Rubber Soul); "Taxman" and "I Want to Tell You" (Revolver); "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" and "Long, Long, Long" (The White Album); and "Something" and "Here Comes the Sun" (Abbey Road).

McCartney notes early in the film that George was recruited because his solo guitar playing was far superior to his or John's. He then became the first Beatle to grow very weary of it all -- the fame, the demands, the secondary status.

"He had the 'love bag of beans' personality -- and the bag of anger," Starr says.

Harrison eventually hooked up with another group of ad hoc mates -- Tom Petty, Bob Dylan, Roy Orbison and Jeff Lynne. They became The Traveling Wilburys, although they never toured. One of the film's high points is footage of their studio rehearsals together. Petty, in a new interview, says that Harrison was completely responsible for forming the group. He also has an amusing anecdote about the time Harrison dropped by to teach him the ukulele -- and then left a bunch of the instruments behind should they ever need them again.

Near the end of his life, Harrison pretty much stayed at home in the Friar Park mansion he had bought and restored. He built a recording studio within, and there's terrific home footage of a proud George mixing some of his son Dhani's guitar work before they give each other hugs.

Harrison otherwise loved tending to his garden or planting trees. And despite Olivia's urging, he had no interest in picking up a latter day slew of awards being offered to him.

"I don't want it," she remembers him saying. "Tell them to get another monkey."

Harrison had a sense of humor, though. Starr cracks him up during their joint appearance on a British TV show. And it's always good to see the outwardly reticent Harrison laugh or cavort, either in a setting such as this or in some of the home movies made available.

Olivia also recounts at length the night a violent, knife-wielding intruder broke into their home. George suffered a collapsed lung and other wounds while he and Olivia likewise bloodied their assailant before police arrived.

His dad, who had survived an earlier bout with cancer, emerged scar-free, son Dhani says. But "it definitely took years off his life."

Starr says he last saw Harrison when he was "very ill, and he could only lay down." He recalls George's last words to him when he said he had to go to Boston to see his daughter, who also had cancer.

"Do you want me to come with ya?" Harrison asked. Starr chokes up before joking, "God, it's like Barbara (f-ing) Walters here, isn't it?"

McCartney isn't one to get misty. What does he miss the most about George? "His humor. His friendship. His love," he replies somewhat generically. Or at least that's what came out of the editing room.

Living in the Material World falls short of Scorsese's terrific two-part PBS film, No Direction Home: Bob Dylan. It lurches about too much at times. And in a three-and-a-half hour film, there's no need to cut some of the performances so short.

Scorsese also barely touches on longtime friend/guitarist Klaus Voormann's first-hand observation that Harrison "stepped back" and began to heavily use drugs again after buying Friar Park. Voormann says he doesn't know why that happened, other than George being a "very extreme" person who plunged into everything full-speed, whether it was "meditation or coke-sniffing." The film leaves it at that.

Olivia Harrison gets the last words, saying that when her husband died, "he just lit the room."

It's clear she means that literally. And it kind of dampens the afterglow of a film that sheds a lot of light on its subject but at times can be a little too blissed out for its own good.

GRADE: B+