Burns' Tenth Inning too often makes errors of omission

09/27/10 12:26 PM

By ED BARK

It might be, it could be, it is -- a strikingly ordinary documentary film from the renowned Ken Burns.

In collaboration with longtime associate Lynn Novick, his four-hour PBS sequel to 1994's Baseball steps to the plate on Tuesday and Wednesday (7 to 9 p.m. central each night on KERA13 in D-FW) as the great game gears up for a post-season that will include the Texas Rangers for the first time in 11 years.

The Tenth Inning begins with Barry Bonds' last game as a Pittsburgh Pirate (Oct. 14, 1992) and his father Bobby's baseball legacy before zooming in on the 1994 strike that killed that year's World Series. But it might better be titled An Increasingly Aggravating Recent History of the Yankees and Red Sox, with Bonds and Steroids Casting a Sinister Shadow.

Burns is a longtime Red Sox fan and Novick is just as devoted to "my Yankees," as she put it in a recent interview with TV critics. And it can't be argued that the period from the strike to the present proved to be very eventful for both teams.

Still, the fixation on them is problematic. As is the exclusion of long-suffering civilian fans. They get no voice whatsoever while media gadfly Mike Barnicle and the likewise over-exposed Doris Kearns Goodwin get to whine and rhapsodize repeatedly about their steadfast devotion to the Red Sox.

"He had tears the size of hub caps streaming down his cheeks," Barnicle says of one of his sons' reaction to Boston's 7th game collapse in the 2003 American League Championship Series against the Yankees. Barnicle says he then asked himself, "What have I done? What have I done?"

Oh shaddup.

Former Yankees manager Joe Torre also is canonized at length for his four World Series championships. Meanwhile, baseball writer Marcus Breton of The Sacramento Bee talks about his pain and suffering as a fan of the Giants, who haven't won a World Series since moving from New York to San Francisco in 1958. Yeah, well at least you've been to two.

The Eastern-centric nature of Tenth Inning -- with trips out West only because of Bonds -- mostly deals out the hardy breeds who have lived and mostly died with the likes of the Rangers, the Cleveland Indians and Chicago Cubs, whose last Series appearance was in 1945 and whose last win came in 1908. The famed Steve Bartman foul ball interference that helped to unravel the Cubs in their 2003 NLCS matchup against the Florida Marlins gets only cursory notice before Barnicle shows up again. This time he bitches about being "humiliated" and "embarrassed" when the Red Sox went down 3-0 to the Yankees before mounting their epic comeback in the 2004 ALCS.

No one should expect Tenth Inning to be as majestic, textured and encompassing as Burns' original Baseball tome. For one, history just doesn't look as good on videotape. Those evocative black-and-white images from the game's distant past -- and the rich color film from the '50s and '60s -- were suitable for framing compared to the Venus Paradise Pencil set nature of the '70s to the present.

Even with the original Baseball, though, Burns tended to cut out the middle part of the country in favor of chronicling the exploits of the Yankees, the Red Sox and the then Brooklyn Dodgers. Case in point: the winningest left-handed pitcher of all-time, Warren Spahn, perhaps got three seconds of screen time. His crime? He played for a small-market team, even if the Milwaukee Braves did manage to smote the mighty Mickey Mantle-led Yankees in the 1957 World Series.

Baseball had the eloquent and recently deceased Buck O'Neill as its inning-to-inning ambassador. No one of his caliber emerges in Tenth Inning, although the Bee's Breton has been extolled by Burns as the "emotional center of gravity in the film," which is back-dropped by Keith David's workmanlike narrative intonations.

The sequel has fresh interviews with Torre, pitcher Pedro Martinez, the Seattle Mariners' groundbreaking Ichiro Suzuki, commissioner Bud Selig, a host of well-known baseball writers and commentators -- and Chris Rock.

Rock appears just once, defending the game's steroid-laced years and tainted home run records by asking, "Who in the whole country wouldn't take a pill to make more money at their job?" Thanks, you've been a great audience.

Bob Costas inevitably is a part of Tenth Inning -- and he at least fully belongs. He's also considerably more indignant than Rock after first noting that the so-called students of the game chart its every little in and out. But "they didn't notice a damn thing when guys showed up looking like they'd been inflated with bicycle pumps!" he exclaims.

Tenth Inning covers the steroid scandal in depth, vividly recreating the titanic Mark McGwire-Sammy Sosa home run battle of 1998, Bonds' epic 73 HR season of 2001 and his eventual over-taking of Hank Aaron as baseball's all-time leader. A telling ballpark banner of those times -- "Ruth did it on hot dogs and beer. Aaron did it with class" -- is nicely juxtaposed with Bonds standing alone in the outfield.

But the film makes little effort to counterpoint all of the juiced stars of baseball with someone who did it without artificial additives. Nolan Ryan comes to mind. His storied career ended right where Tenth Inning begins. But the filmmakers pay him no mind, instead training on the over-40 accomplishments of the now badly soiled Roger Clemens.

Tenth Inning also details the latter day infusion of star Latin ballplayers, but makes no mention of the concurrent shrinking number of black players. Burns' Baseball was at its best in depicting Jackie Robinson's breaking of the "color line" and the colorful history of the talent-rich Negro Leagues. But the now voluntary and ironic exodus of blacks to sports other than baseball gets nary a second of air time in Tenth Inning.

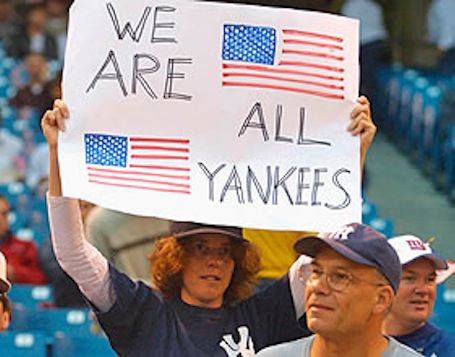

Burns has made many exemplary films for PBS. But Tenth Inning is at best a bloop double in comparison to home runs ranging from The Civil War to Jazz to Baseball. Too often it seems like a competent but hardly inspired highlight reel, replete with lengthy looks at Yankee/Red Sox triumphs and heartbreaks. Amazingly, though, Burns and Novick fail to include President Bush's perfect strike to open Game 3 of the highly emotional 2001 World Series at Yankee Stadium between New York and the Arizona Diamondbacks.

That was high drama, with the sell-out crowd giving Bush a standing ovation as he entered and chanting "U-S-A, U-S-A" as he left. Love of country, love of baseball, intertwined in one of the great signature moments in baseball history. But it didn't make the cut. Because after all, Mike Barnicle still had things to say.

GRADE: C+