HBO's The Curious Case of Curt Flood is about far more than baseball

07/12/11 02:39 PM

By ED BARK

As a kid who loved the lowly Chicago Cubs, I regularly loathed Curt Flood for robbing the likes of Ernie Banks or Ron Santo with one of his trademark leaping catches as the star centerfielder of the St. Louis Cardinals.

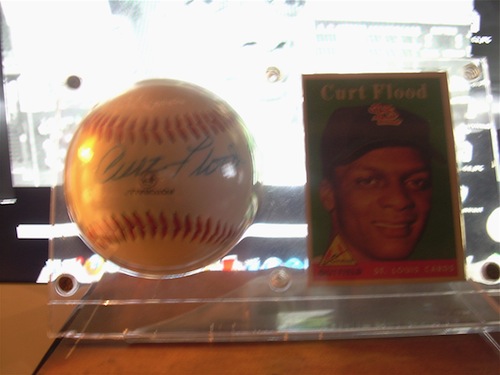

As an adult at the 1995 All-Star Game Fanfest in downtown Dallas, I got a chance to remind him of what he'd done. We both laughed about the pain he'd caused before he signed a baseball in his role as one of the event's featured guests. I later bought his rookie card and have kept both ever since in the plastic contraption you see above.

HBO's excellent The Curious Case of Curt Flood, premiering Wednesday at 8 p.m. central on the day after the All-Star Game, reminded me anew of Flood's off-field pursuit of free agency in times when team owners had sole control of their players' careers. It also fills in a lot of blanks about this willful, proud and in many ways self-destructive nomad. It turns out that Flood first developed a cough he couldn't get rid of during his brief time in Dallas for the All-Star Game at what was then The Ballpark in Arlington. He died of throat cancer on Jan. 20, 1997 after years of heavy smoking and drinking.

The 90-minute HBO documentary, one of the very best in a long line of standouts, is in no way a pity party for Flood. His neglect of his children and his apparently fraudulent side business as a portrait painter are all parts of his story. But there is redemption as well, with Flood finally finding his way back toward stability and respectability in the few years he had left before dying at age 59.

Scarred by racial prejudice as a young ballplayer -- as were many of his black peers -- Flood was just 31 and still at the top of his game when he learned he'd been traded to the Philadelphia Phillies along with Cardinals teammate Tim McCarver.

"You were traded just like cattle or pigs or hogs or anything," recalls McCarver, who remains very much a part of the game as a Fox Sports analyst who's again teaming with Joe Buck for Tuesday's All-Star game.

But McCarver dutifully reported to the Phillies while Flood took baseball to court as part of an "anti-trust" lawsuit and his quest to become a free agent.

"I'm a well-paid slave, but nonetheless a slave," he told Howard Cosell. This endeared him to basically no one, given his $90,000 yearly salary at the time. Flood also would have received a $20,000 raise had he joined the Phillies. On principle, he decided to stay the course while current-day players went about playing ball and either openly opposing Flood or putting his cause behind them.

One of his Cardinals teammates, fearsome fastball pitcher Bob Gibson, remains alternately hardened and sympathetic toward Flood, who narrowly lost his U.S. Supreme Court case in the absence of any visible support from current-day players.

"I wouldn't have shown up. No," the current-day Gibson says of any thoughts he might have had about standing beside Flood during the Supreme Court hearing. He also disparages Flood for running off to other countries, including Denmark and Mallorca, Spain, rather than facing up to his family responsibilities. But Gibson also was one of Flood's pallbearers. And he clearly is close to tears while describing his old teammate as a great ballplayer and "one of the best friends that you could ever have."

Flood eventually had an epiphany, as did Mickey Mantle after years of drunkenness and self-indulgent behavior. And his off-the-field legwork led to the landmark free agency breakthrough by pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, who accomplished what Flood set out to do via collective bargaining instead of the court system.

The Curious Case of Curt Flood draws its power, however, from the portrait it paints of a flawed, unfulfilled, oft-wayward soul whose talents and temperament imploded on him. After his defeat in court, he scraped his way back to the cellar-dwelling Washington Senators for a 1971 season that ended in his sudden disappearance. His baseball talents eroded beyond repair, Flood clandestinely retreated to Spain, opened a bar and gradually immersed himself in new miseries of his own making.

But still he returned to the living, striving to make amends with his children and reuniting with an old girlfriend, Judy Pace Flood, who demanded his sobriety before she'd marry him. She now speaks volumes as his widow. Shelly Flood, one of his daughters from a failed first marriage, communicates both the pain of abandonment and the healing that had only just begun. One of Curt Flood's former girlfriends, Karen Brecher, also provides considerable insight into his later years.

Many old-line baseball fans might still blame Flood for "ruining" the sport, even though he ended up striking out in the Supreme Court. But more than 40 years after he declared his intentions, it's hard to argue with Flood's declaration of independence in a letter to the plaintiff in his case, baseball commissioner and company man Bowie Kuhn.

"After twelve years in the major leagues," he wrote on Christmas Eve, 1969, "I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes."

He sacrificed a lot. He also repeatedly indulged himself at the expense of others. The Curious Case of Curt Flood tells it all -- except for the many extra base hits he took away from the Cubs of my youth.

GRADE: A