Jun 2008

Ch. 5's Bobbie Wygant kept seeing stars and knew what to do with them

26/06/08 11:13

Note to readers: Roberta Connolly "Bobbie" Wygant joined KXAS-TV (then WBAP) at its creation in 1948. She eventually became best known for her steady stream of celebrity interviews and movie reviews before retiring from full-time work at the station in 1999. She still regularly contributes freelance pieces to NBC5, though. This article, first published on March 8, 1981, looks at how Wygant aimed for the stars without shooting them down. In return she expected a performance of sorts. It all worked out pretty well for her.

By ED BARK

Whether suffering at the little hands of Ricky Schroder or showing Dustin Hoffman a genuinely good time, Bobbie Wygant is unfailingly buoyant and undeniably professional.

Her monthly Entertainment and the Arts specials are Channel 5's avenue to the stars. It's obvious she primps and prepares for each celebrity. In return, she expects more than just the time of day from notables promoting their latest activities.

"A lot of stars get very uptight about interviews," Wygant says. "They just are in a nervous tizzy. So many of your television stars are people who have very little background in the business. And there's nobody trying to help them.

"It's such a mill and a factory. It's not like the old studio days where they actually learned how to give good interviews. They learned how to dress for a picture session. Not only did they learn, but they had to pass inspection, as it were. Now I see actors and actresses coming in and schlepping around, looking like they just came in from washing the car. In the old days that would never have happened."

For Wygant, the "old days" date to 1948, when she joined Channel 5 after graduating from Purdue University. In 1960, she got her own program, Dateline. It was a "basic local interview show" that ran for 14 years until Lin Broadcasting brought Channel 5 in 1974.

"I used to say, 'If it isn't illegal or immoral, I'll put it on,' " Wygant recalls.

Her next assignment was a 5 p.m. "magazine format" program co-hosted by Chip Moody. In 1977, the station switched to "hard news" at 5 p.m. and Wygant found herself in limbo for a while. News director Bill Vance wasn't sure he could afford a full-time "entertainment and the arts person," she says. Eventually, Channel 5 decided it couldn't afford to lose her. And so she endures as the only Dallas-Fort Worth television performer with a regularly scheduled half-hour celebrity showcase.

"As they say in television, 'working quick and dirty,' I think I do a good job," Wygant says.

Quick and dirty means an allotment of about 10 minutes per star. When she travels to New York or Los Angeles, Wygant often is one of 30 reporters penciled in for a brief interview. The time constraints are relaxed a bit when celebrities come to Channel 5's Fort Worth studios.

"I'll try to find some angle so they're not just sitting there doing the commercial to get people to go see the picture," Wygant says. "I try never to be in awe of them because I think the minute they sense that, it does something to the professional relationship. I don't want to sit there like some little teenybopper and say, 'Ooh, I just love you.' It's not my nature to do that.

"I read people pretty well," she adds, noting her double major in psychology at Purdue. "I don't come at them as if they were on the witness stand and I'm a prosecuting attorney. I find giving them a little gentle jab sometimes works just as well, if not better. I've seen other interviewers just really strike out, and their subjects just drop the curtain and clam up."

She had a memorable conversation with Hoffman after opening the interview with a simple, disarming, slightly naughty question. Wygant noted the somewhat reclusive actor was doing hundreds of interviews for the film Kramer vs. Kramer after refusing to tour the country on behalf of the many other movies he'd made since The Graduate.

"Why are you working your buns off?" she asked him.

Hoffman seemed genuinely charmed by the question and loosened up immediately. He offered a humorous discourse on his "buns" and then gave long, thoughtful answers to Wygant's other concise questions.

After the formal session ended, Hoffman said, "She's all right. That was a great interview. Who's your sponsor, Hot Cross Buns?"

It's all on tape, as is a somewhat less scintillating interview with Schroder, the child star, who recently visited Dallas to promote The Earthling. Virtually all of his answers were quick one-liners, but the indefatigable Wygant continued to pump questions, never pausing, using every second of the time allotted to her. A less prepared interviewer might have either given up or been reduced to a stammering mess.

Sometimes grown-up stars can be a problem, too. Wygant says her most disappointing interview was with Charlton Heston, who was supposed to be touting the movie Will Penny.

"His answers were, 'Well . . . uh . . . er,' and he just ate up time with that," she recalls. "I was livid with him because I knew I was giving him good stuff and he wasn't cooperating. Later I found out he was unhappy because it was a beautiful day and he wanted to play tennis."

Wygant says she had better luck in subsequent interviews with Heston, who has been "dynamite" since fizzling.

While promoting 9 to 5, Jane Fonda got a bit miffed when Wygant asked her what kind of president Ronald Reagan would be.

"When the interview was finished, Jane said, 'I bet you didn't ask Dolly Parton that.' "

"I sensed a little edge to her voice," Wygant says. "She said nobody thinks she has a sense of humor because they always ask her the serious and news-related questions."

"But Jane, you speak out on these things," Wygant says she told the Oscar-winning actress. "Even if people don't ask you, you're vocal with your opinions and you have taken stands. You're a natural person to ask questions like that.

"I think sometimes it isn't what someone says, but how they say it," Wygant says. "I like animation. And of course, you want them to directly answer the question. You know there are some people who you ask the time and they tell you how to build a watch. I want something people will perk up their ears to listen to, but I don't like people who work at being provocative. The good people are the ones who make it seem spontaneous, no matter how many interviews they've done."

Wygant says she won't ask questions that invade a celebrity's privacy. Otherwise, though, she'd like them to tell it all in an entertaining manner. In her case, there is one non-answerable question. Her biography includes information on her husband (former Channel 5 executive Philip Wygant), their homes and a cabin cruiser named Good Grief. There's no birthdate, though.

"If you were to print my age, there would be people who would immediately hold that against me," Wygant explains. "As long as we're in a youth-oriented society, middle-aged men and women should forget about their age. It doesn't serve me well to give mine, so I finally said, 'The hell with it.' "

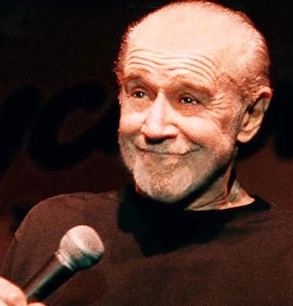

George Carlin: May 12, 1937 to June 22, 2008

23/06/08 06:44

Note to readers: George Carlin's death Sunday of heart failure ended his oft-stormy reign as the fiercely independent elder statesman of take-no-prisoners comedy.

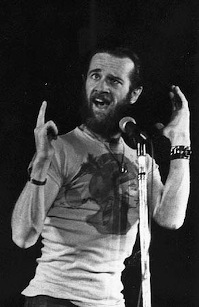

His comedy roots date to a radio deejay job in Fort Worth, where he met and teamed with Jack Burns. They left for Hollywood in 1960 and broke up two years later. Carlin branched out on his own, initially in a clean-cut guise as the "Hippy Dippy Weatherman." But by the late 1960s, he had grown a beard, long hair and was spouting his famed "Seven Words You Can Never Say on TV."

Those words got him arrested during a famed 1972 "Summerfest" concert performance in Milwaukee. He was charged with disturbing the peace, but a Wisconsin judge threw the case out of court.

Carlin, ever unrepentant, went on to make a record 14 comedy specials for HBO and also hosted the first episode of Saturday Night Live on Oct. 11, 1975.

The below article originated that same year in the pages of the University of Wisconsin-Madison student newspaper The Daily Cardinal. It includes both a review of Carlin's performance and a still unforgettable interview with him backstage. Warning: the article contains some hard-core profanity that we somehow managed to get in the paper 33 years ago. It's all being left in because obviously Carlin would have wanted it that way. It's who he was.

By ED BARK

George Carlin is the only comedian around who can do 10 minutes on farting -- and walk away smelling like a rose.

"Did you ever notice that your own farts smell OK?"

"It's just exhaust. We're not perfected yet."

"You know you really like your neighbor or your partner when you're willing to fart out loud."

Does he have to talk that way? Why does he say those things?

Well, Carlin's just warming up. But let him explain. It's backstage at Madison's Dane County Coliseum, where Carlin has just reimbursed 3,000 souls who paid him to make them laugh long and hard.

"Anything we all do and never mention, I think is funny, ya know? It can be anything totally universal which is practically completely ignored in conversation. When the spark jumps between those two, it's magic. It produces laughter because it's a surprise."

This of course is not Al Sleet, the Hippy Dippy Weatherman talking. Or sportscaster Biff Barf. Or Willie Wise, the wonderful WINO disc jockey. Carlin "doesn't hang out with them anymore." He shucked the show lounge scene after undergoing a late-sixties metamorphosis.

"Those places died in 1945 and they forgot to lie down," he says. "I was just sick to my stomach of wearing the dumb tuxedo and entertaining middle class morons."

So tonight Carlin wears a captioned t-shirt ("On the back of this shirt is a true statement." Flipside: "On the front of this shirt is a false statement.") and matching blue jeans. He says he was 16 in '53. He looks 50 in '75. His forehead is plowed with deep furrows. Old gray hair ain't what it used to be a few years back. He wears rimless glasses offstage, the same kind the nuns who taught him at New York's Corpus Christi grammar school used to wear.

And he now "looks at the world at a 45 degree angle." From that perspective, you examine things a little closer. You look at things a lot differently.

"Snot's funny. The original rubber cement, ya know. Ya can't get rid of it."

"What do dogs do on their day off? They can't lie around. That's their job."

"In New York subways, it's a $50 fine for spitting. Vomiting is free."

Carlin onstage is a mixture of improvisation and oft-told bits. He's got rhythm on the brain. If something doesn't go just right, he'll cue the audience: "I didn't have the right rhythm on that one."

He'll dig a grave for himself occasionally; sometimes you're not quit sure whether he'll bail out. But he always does. And when he's really rollin', he leaves 'em laughin' -- hard.

"You know yourself that when you're telling a story to someone, and they laugh, you're thinking why they're laughing," Carlin says. "That's the logical way to entertain. So with that in mind, with a long laugh from an audience, when you're struttin' a little bit, if you're articulate that night, that's when you have fun improvising. Same paint box. Different paint."

Thinking on your feet. That's something alien to national institutions like Bob Hope and the late Jack Benny.

Carlin says Hope "doesn't have the soul of a humorist. He's a fascist. I'm glad he learned how to make wisecracks. But I don't think he ever had any original ideas.

"Some performers don't write or conceive of things. They're joke tellers and laugh getters. They draw from a sort of public domain pool of jokes. Some them are just better than others at it."

Jack Benny's predictable routines were "okay for their time. He was cheap, he was 39 forever, he had great delivery and knew which jokes to reject. But I don't think he was a humorist."

Some of Carlin's "heroes" are Danny Kaye, Ernie Kovacs, Steve Allen ("when he was really trying and using his brain"), the Marx Brothers, Ritz Brothers, Bob Newhart ("at his best in the beginning") and the catalyst, Lenny Bruce.

Like Lenny Bruce, Carlin is fascinated with words and names. He loves to play with them and twist their meaning out of shape.

"Names. They mean something. For instance, you wouldn't buy Goodyear pancakes. No one wants those. You wouldn't want Aunt Jemima tires for the same reason. If Janitor in a Drum made a douche, nobody'd buy it."

He explores the inside/underside of mass fascination in exhaustive detail. As did Lenny Bruce. Football and baseball, for instance. Have you ever looked at them this way?

"Woody Hayes is weird. He wears a baseball hat during football games. Can you imagine if Walter Alston wore a football helmet during a baseball game? They'd take him away in a wire truck."

"Football is a ground acquisition game. You beat the shit out of 11 guys and take their land away from them. 'Course you only do it 10 yards at a time. That's the way we handled the Indians, right? First down in Pennsylvania, Midwest to go."

"The language of football and baseball tells it all. Football is technological. Baseball is pastoral. Football is played on an enclosed grid. Baseball is played on an ever-widening diamond reaching into infinity."

"In football you have the hit, clip, block, crackback, the tackle, the blitz, the bomb, the offense, the defense. In baseball, you have the sacrifice."

Carlin is into drugs, although less so now. So, tragically, was Lenny Bruce.

"I was a pot smoker since I was 13," Carlin says. "At 21, stoned habitue. It's a permanent value changer. If you smoked only for a week when you were 16, and you thought about a lot of shit during that week, and you never smoked again, you'd be making decisions at 48 that would be somewhat different. I believe that."

Prior to the transformation, he took "just about the right amount of acid to make the changes that it can help many people make."

But it's Carlin's hit-over-the-head usage of "dirty" words that evokes the most vivid comparisons. Lenny Bruce paved the way and paid with his psyche. For Carlin, the roadwork is not yet finished. He's expanding his list of "seven dirty words you can't say on TV."

"I added fart, turd and twot. These three, of course, were the only ones selected this year and inducted into the Hall of Fame, as it were. We're inspecting all of them. Dingleberry almost made it this year."

And the grand finale. It's Carlin's crusade. Or so it seems.

"The person who thought up the slogan, 'Make Love, Not War,' . . . his job was over that day. He could've retired at that moment. If it would've been me, I would've walked away. So long, I'm goin' to the beach. You guys work it out."

"Now I have a slogan, too. It's not as euphonious. It doesn't roll off the tongue. It's 'Make Fuck, Not Kill.' Substitute the word 'fuck' for the word 'kill' in all of our writings. I'd love to see it. Just for awhile. Just for a year or so. And we would change."

"Ya know, they tell me society sucks. I wish they'd get started."

Carlin won't do "college circuit" comedy forever. It's a drain; sometimes you don't know if your rap is making sense. Video beckons.

"If you're a storyteller, you've gotta try all the ways, that's all," he says. "Adding a soundtrack and putting in a monster screen, and being able to edit it . . . you oughta be able to do good stories. I gotta find that out."

Whatever happens, whatever Carlin does, he'll remain an intensely human specimen, shot full of the heightened insecurities and paranoia that plague every standup comic. Sometimes they surface, as they did outside the Coliseum.

A frail figure runs toward us. It's Carlin.

"Hey, before you leave, I just wanna ask you something. Did I sound like I was full of shit? Ya know, sometimes, after I've been talking for a long time . . ."