Ken Burns' Prohibition a rollicking/sobering look at America's nearly 14-year drinking game

09/30/11 02:02 PM

By ED BARK

The bar has been raised pretty high for Ken Burns. And that goes double for Prohibition, which after all is about drinking, the drive to end it and the abject failure to do so.

His vast portfolio of acclaimed documentary films for PBS dates to 1981's Brooklyn Bridge. The format remains the same: a blend of expert commentaries, celebrity voiceovers of historical figures, archival footage and stills, and mood music from three main sources -- pianos, horns, violins. This time keyboards have an upper hand.

The disparate topics are their own distinctive driving forces, though, with Burns and his longtime collaborator, Lynn Novick, sifting, winnowing and finally settling on what they hope will be just the right mix of audio and visual. Their new film is a masterpiece in that regard. It runs for five-and-a-half hours from Sunday, Oct. 2nd through Tuesday, Oct. 4th (7 p.m. central each night).

Prohibition of course is sobering at times. But it also can be almost riotously amusing in its depictions of what Prohibition wrought. Gangland violence wasn't exactly a blast. But speakeasies, flappers, the Charleston and a party girl columnist for The New Yorker -- whose pen name was "Lipstick" -- put a lot of bounce in this long look at the 18th amendment to the Constitution and its eventual repeal via the 21st. It's all perfectly narrated by Peter Coyote, who sets the table by observing that Prohibition "was meant to eradicate an evil. Instead it would turn millions of Americans into law breakers."

Sunday's opening chapter builds to the climactic Jan. 17, 1920 enactment of Prohibition after a series of false starts and scare tactics. Its early advocates aren't entirely dismissed as close-minded, wrong-headed buzz killers. Alcohol consumption, mostly on the part of men, amounted to an epidemic way of life that led to early deaths and oft-brutish treatment of women who feared the arrival home of their drunken husbands.

"Americans routinely drank at every meal, including breakfast," Coyote says.

Activists such as Eliza Jane Thompson and Frances Willard led marches and prayer vigils against demon rum and other forms of alcohol. They were taunted and in some cases stoned by saloon patrons. It was an early, primitive form of women's liberation, marked by considerable bravery on the part of those who dared to make their voices heard after years of staying at home, minding the children and wondering how they'd make ends meet after their husbands drank away the family income.

Carrie Nation, best known among the early protestors, literally took matters into her own hands by entering what were supposed to be illegal saloons in Kansas and smashing away at them with a hammer and other implements. Bar owners took to putting up signs reading, "All Nations Welcome Except Carrie."

None of this really worked. But then came the establishment of the federal income tax. From thereafter, "the government would no longer have to rely on alcohol (taxes) to fund its operations," Coyote says.

The film also notes that many advocates saw Prohibition as a way to keep alcohol away from immigrant Americans and blacks, who were seen as inferior classes with little class when it came to the bottle. Veteran New York journalist Pete Hamill, never one to mince words, says that strict Prohibition constructionists would have imprisoned Jesus for turning water into wine. That kind of distills it.

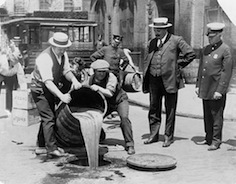

Keeping alcohol from the public never worked from the start. What America couldn't have was what America desperately wanted. And no amount of raids or other law enforcement tactics could quash the booming business in speakeasies or showy gangsters such as Chicago's Al Capone.

Burns uses former Dallas Morning News sports writer Jonathan Eig as his Capone expert. Eig's growing number of non-fiction books includes Get Capone. He says that the notoriously popular bootlegger "was the first media hound, the first publicity addict among the great gangsters." He held press conferences and bought off cops, politicians and reporters, reasoning that favorable copy about him would dupe the public because "most people are stupid enough to believe what they read in the newspapers." Capone also made the cover of Time.

Other colorful characters abound, including 1928 Democratic presidential candidate Al Smith, who flamboyantly campaigned for repeal of Prohibition with the zeal of this year's crop of Republican candidates pledging to overturn "Obama care." But Herbert Hoover won election in a landslide after his allies branded Smith a dirty, drunken Catholic who would make illegal aliens of Protestant children and planned to build an underwater tunnel to the Vatican. Or at the very least allow the Pope to live in the White House.

That sounds pretty hilarious on paper, but some people bought it. Which meant that Prohibition endured through the Great Depression, which occurred on Hoover's watch and turned legions of his supporters against him. In the end, repeal of Prohibition essentially was viewed as a desperately needed jobs bill, with thousands of destitute Americans legally allowed to find employment in the beer and hard liquor industry. It all officially ended on Dec. 5, 1933 under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

This is only scratching the surface of Prohibition, which vividly and entertainingly recaptures an almost impossibly absurd era. In the end, it may be the most fun you'll ever have with a Ken Burns film. It probably will make you thirsty as well.

GRADE: A