Stellar Salinger documentary film makes "director's cut" premiere on PBS

01/21/14 08:49 AM

By ED BARK

@unclebarkycom on Twitter

Some still call him “Jerry,” which seems the equivalent of making Lawrence of Arabia a “Larry.”

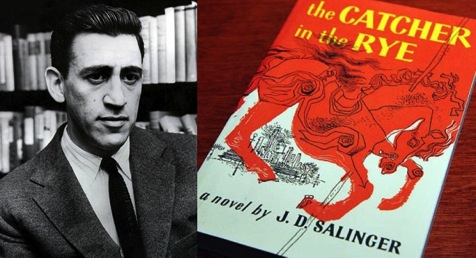

But literature’s version of Greta Garbo didn’t always play hard to get or fathom or approach. J. D. Salinger, whose The Catcher in the Rye made Holden Caulfield a Huck Finn for the contemporary disaffected, used to be out and about with friends and associates. Many are still around to tell tales about him in Salinger, which has its television premiere with an elongated two-and-a-half-hour “director’s cut.” (In D-FW, the documentary film airs from 8 to 10:30 p.m., Tuesday, Jan. 21st on KERA13.)

Presented as the 200th episode of PBS’ long-running American Masters series, Salinger is an engrossing true-life detective story with dramatic flourishes, sobering revelations and, of course, ”never-before-seen” photographs and footage of its subject. He died on Jan. 27, 2010 at the age of 91 without ever doing an on-camera interview. Nor are there any audio recordings of Salinger, whose last work was published in 1965 while he continued to write in solitude in “The Bunker” adjoining his Cornish, New Hampshire home.

Filmmaker Shane Salerno spent 10 years in search of the “real” Salinger, a World War II veteran of D-Day and other combat who very well may have emerged shell-shocked forevermore. An excerpt from a rare 1944 letter home reads: “I dig my fox-holes down to a cowardly depth. Am scared stiff constantly and can’t remember ever having been a civilian.”

The Catcher in the Rye was published in 1951, several years after Salinger finally achieved his lifelong ambition of having a short story published in The New Yorker. It was titled “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” and first appeared in print on Jan. 31, 1948 (your friendly content provider’s birthdate, oddly enough).

Salinger’s close friends in the early days included the biographer A.E. Hotchner, best known for his 1966 book Papa Hemingway. The pre-war “Jerry,” as he calls him, “really came from a country club society” and used to greatly enjoy parties and bars. But his friend became a friend no more after Hotchner “betrayed” him by inadvertently allowing Cosmopolitan magazine to change the title of one of Salinger’s short stories even though every word of it remained as written.

“His face turned apoplectic red,” Hotchner recalls. And then Salinger walked out. Period. End of story. “He sort of became the Howard Hughes of his day,” Hotchner says.

Salinger easily took offense and then turned further inward. In his post-World War II days/daze, he preferred the company of much younger women after a puzzling marriage abroad to Nazi Sylvia Luise Welter. It ended a month after they returned to the United States, and of course remains otherwise shrouded in mystery.

Salinger then met 14-year-old Jean Miller on the beach at Daytona. He was more than twice her age at the time.

“I was fresh and new, like a breath of spring,” Miller says unaffectedly. They had a platonic relationship, she says, taking long walks on the beach while also conversing at length.

Miller turned 18 in 1954. And “once in a while he would come and fetch me,” she says. He was ensconced in Cornish by then. They’d take walks, have dinner, watch TV and sometimes dance together. “But there was never an inkling of anything physical between us,” Miller says, until the day she initiated a kiss and later went to bed with Salinger. She told him she was a virgin, “and he didn’t like that . . . I knew I had come between him and his work. And it was over.”

Miller’s interview is both stark and affecting in its candidness. But the film’s most revelatory segments are with novelist Joyce Maynard, who was 18 when an article of hers in The New York Times Magazine aroused Salinger’s interest. He wrote her regularly and “there was never any question that we would meet,” Maynard says.

They lived together in his home for 10 months, adhering to Salinger’s set routines while Maynard worked on her first novel.

“He cut himself off from a great deal of the world, but maintained a huge interest in observing it,” she says. But of course this didn’t last.

“I think he was indulging in a fantasy of innocence that neither of us could hold onto very long,” says Maynard, whose 1998 memoir, At Home in the World, revealed her relationship with “Jerry.” She was spurred to do so after finding that he had written a “surprising number” of letters to young girls, one of whom became his third wife. The documentary includes a searing denouncement of Maynard by Jon Stewart. It now seems more than a bit excessive.

Salinger also shows seemingly every clandestine photo snapped of Salinger in his later years. The “last recorded images” are in color and on video. They show Salinger walking with a cane in the company, presumably, of his third wife. He’s last seen smiling from the passenger seat of their car.

The “director’s cut” version includes some interviews that easily could be cut anew. Danny DeVito comments very briefly for some reason. Observations from Jane Kaczmarek, Edward Norton Judd Apatow and Philip Seymour Hoffman likewise are largely extraneous.

Salinger triumphs, though, as an absorbing portrait of a singular man of mystery. Filmmaker Salerno hits on every conceivable touchpoint while being shackled by legal restrictions that prevented him from “quoting virtually any of Salinger’s work on camera or from having anyone read or perform any of Salinger’s work,” according to PBS press materials.

Still, he has broken through these barriers and captured the essence of perhaps the most elusive subject in the land -- in life or in death. Then again, “Reclusivity is a great public relations device among other things,” says acclaimed novelist E.L. Doctorow.

Indeed.

GRADE: A

Email comments or questions to: unclebarky@verizon.net