Legend of Lead Belly makes Smithsonian Channel worth a look

02/20/15 12:27 PM

By ED BARK

@unclebarkycom on Twitter

He lived in hard times, did a lot of hard time and like many black artists of his era became appreciated more in death than life.

Smithsonian Channel’s one-hour docu-film, Legend of Lead Belly (Monday, Feb. 23rd at 7 p.m. central), serviceably recaptures the Rock and Roll Hall of Famer’s impact on what turned out to be mostly white musicians.

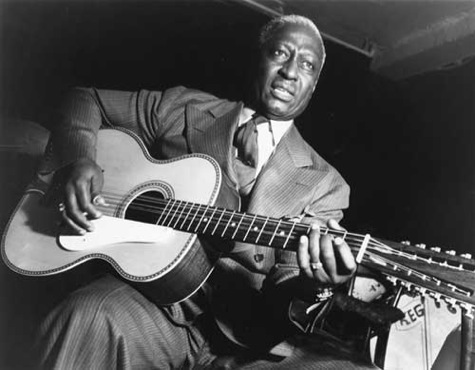

His most famous song, “Good Night, Irene,” became a huge hit for The Weavers in the year after his death on Dec. 6, 1949. Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter’s last performance was at the University of Texas at Austin, where his vocals remained strong but his signature 12-string guitar playing was impaired by Lou Gehrig’s Disease. He was 61 and had spent a good number of his earlier years in Louisiana and Texas prisons after convictions for various violent crimes. The 1935 edition of the New York Herald Tribune included the headline, “Sweet Singer of the Swamplands Here to Do a Few Tunes Between Homicides.”

“It was more like he (Lead Belly’s white manager, John Lomax) was presenting King Kong,” says bluesman Chris Thomas King in a new interview for the film.

Van Morrison, Judy Collins, Roger McGuinn (leader of The Byrds) and Robby Krieger of The Doors also are called on to praise Lead Belly’s contributions.

“I think the spirit of the songs that Lead Belly did is indestructible,” says McGuinn. Besides “Good Night, Irene,” they included “The Midnight Special, Rock Island Line, Where Did You Sleep Last Night?, Black Betty” and “House of the Rising Sun,” which brought The Animals to prominence in 1964.

Lead Belly’s Texas connections also include Dallas’ Deep Ellum district, where as a 23-year-old he teamed with Blind Lemon Jefferson. But five years later, in 1917, he was convicted of murder and sentenced to Shaw State Prison in Huntsville, TX. Amazingly he regained his freedom seven years later via a successful singing petition for his pardon to Texas governor Pat Neff.

Several years later, though, Lead Belly went back behind bars, this time to Louisiana’s notorious Angola Prison after being convicted of attempted homicide. He continued to entertain inmates with his songs and guitar. And in 1933, folklorist John Lomax and his son, Alan, came calling with primitive recording equipment and an intent to document authentic “Negro work songs.”

Lead Belly eventually found some peace with his marriage in 1935 to “longtime girlfriend” Martha Promise. They stayed together for the rest of his life, even though Lead Belly was constantly hitting the road and the bottle. He was with Martha on a trip to Washington, D.C., though, where the film says they were turned away from a whites-only rooming house. Lead Belly responded by writing “Bourgeois Blues,” with lyrics that included, “Home of the brave, land of the free. I don’t want to be mistreated by no bourgeoisie.”

He had never had a hit record on his own, but was embraced by the likes of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie as an authentic protest singer. They wore jeans and work shirts during appearances together while Lead Belly always appeared in stylish suits. The film notes the irony.

Legend of Lead Belly is narrated by actor Clarke Peters, who sometimes overdoes it a bit. The film lacks the texture, nuance and artful editing that tend to go hand in hand with Ken Burns. It’s an interesting primer, though, extolling “one of the most influential musicians you’ve never known,” according to publicity materials.

That pretty much says it, with Legend of Lead Belly filling in some of those blanks.

GRADE: B-minus

Email comments or questions to: unclebarky@verizon.net